Alternative

We Can Work It Out: The Inside Story Of How Nike’s Ad Featuring The Beatles’ “Revolution” Started A Legal (And Advertising) War That Eventually Gave Peace A Chance

In 1987, the Beatles licensed “Revolution” to Nike to feature in a commercial that’s come to be considered one of the best ads of all-time. Then, almost immediately, the Fab Four filed a $15 million lawsuit against the sneaker company for using their song in the commercial. Nike’s Mark Thomashow, who set up the deal, […]

The post We Can Work It Out: The Inside Story Of How Nike’s Ad Featuring The Beatles’ “Revolution” Started A Legal (And Advertising) War That Eventually Gave Peace A Chance appeared first on Magnet Magazine.

Published

2 years agoon

By

adminIn 1987, the Beatles licensed “Revolution” to Nike to feature in a commercial that’s come to be considered one of the best ads of all-time. Then, almost immediately, the Fab Four filed a $15 million lawsuit against the sneaker company for using their song in the commercial. Nike’s Mark Thomashow, who set up the deal, sat down with MAGNET’s Corey duBrowa to explain what really happened behind the scenes in a tale that not only started a very real legal (and advertising) revolution, but also involved everyone from Michaels Jackson and Jordan to Julian Lennon and his dead father’s ghost.

Chapter 1: They Said They Wanted Revolution

Sued by the Beatles! Causing this type of headline is not a career-enhancing move at most corporations. Luckily for me, Nike is not most corporations. In 1987, I was an associate corporate counsel in Nike’s legal department. I was responsible for the legal work related to Nike’s advertising and sports marketing needs, which included negotiating for the talent and music that appeared in Nike ads.

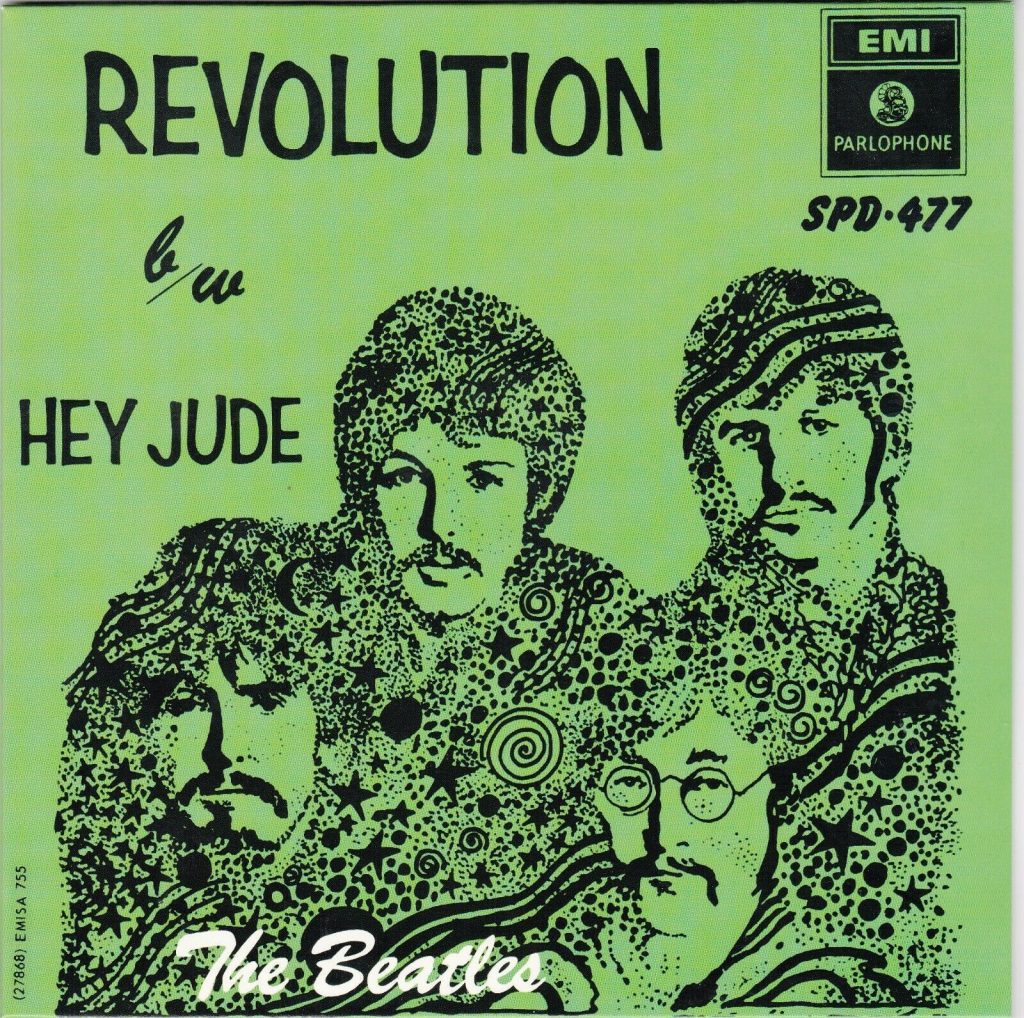

Nike was ready to introduce the Air Max, the first shoe with visible air. Its introduction was anticipated to be a game changer for the company. Nike had tasked its ad agency, Wieden & Kennedy (W&K), to create an ad campaign appropriate for the introduction of a groundbreaking—ahem, revolutionary—new technology. W&K over-delivered when they presented a concept using Nike’s premier athletes (as well as everyday athletes) to be filmed with hand-held cameras and accompanied by the Beatles’ “Revolution.” No one had ever licensed a Beatles song performed by the Fab Four in an ad to that point. And no one has since.

In December 2015, I thought that unique distinction by Nike had come to an end when I was startled by a television ad featuring scenes of the Beatles from Yellow Submarine. Other visuals included album covers, footage and photos of the Fab Four, etc. The soundtrack contained several Beatles songs. I waited with anticipation to see whether another company had secured the rights to a Beatles master. I was relieved to see it was an ad for Google Play [Full disclosure: Corey duBrowa now works for Google] for the streaming of Beatles music—i.e., Beatles music selling Beatles music. Nike retained the distinction of being the only company to use a Beatles master to promote its own product.

The “Revolution” ad debuted Thursday, March 26, 1987, on NBC’s top-rated The Cosby Show. On July 28, Apple Records filed suit against EMI Records, Capitol Records, Nike and W&K for $15 million, claiming damages for the use of the song. I had been in Nike’s legal department for four-and-a-half years at the time of the Beatles’ lawsuit.

After the suit was filed, I moved to Nike advertising and started the business affairs (BA) function, which I headed from 1989 until I retired in August 2015. BA had the responsibility to secure the rights to do the ads Nike wanted to create. This involved licensing music, negotiating for talent to appear in the ads, licensing animated characters, as well as getting permission from various sports leagues, teams and associations to use their marks as part of Nike’s efforts. Prior to about 2010, all of the significant talent deals were negotiated exclusively by BA. Since then, talent deals have become a joint effort with Nike Global Entertainment Marketing (GEM).

The stories I’ll be telling are limited to the deals I did.

I often tell people that Nike moved me from legal to advertising after the Beatles suit because they felt I’d do less damage in advertising than I had done in legal. A nice story—self-deprecating, to be sure—but not really true. The move was prompted because I had delivered the seemingly undeliverable: a Beatles track for an ad. Nike thought I showed promise in securing the rights and talent it needed for its ads. The story behind how Nike got “Revolution” is a great way to frame what many consider to be the best advertising done by any company, in any industry, ever.

Chapter 2: How To Start A Revolution

Two licenses are needed to secure a song for advertising purposes: one from the music publisher, who controls the music and lyrics, and one from the record label, which has the rights to a particular artist’s recording of the song. The North America rights to distribute Beatles music were controlled by Capitol Records, under a license from the Beatles’ label, Apple Records. As a side note, Apple Corps, the holding company that owns Apple Records, has been involved with Apple, Inc. (of iPod, iPad and iPhone fame) in litigation for a number of years on trademark-infringement issues. Indeed, the Beatles were not litigation adverse.

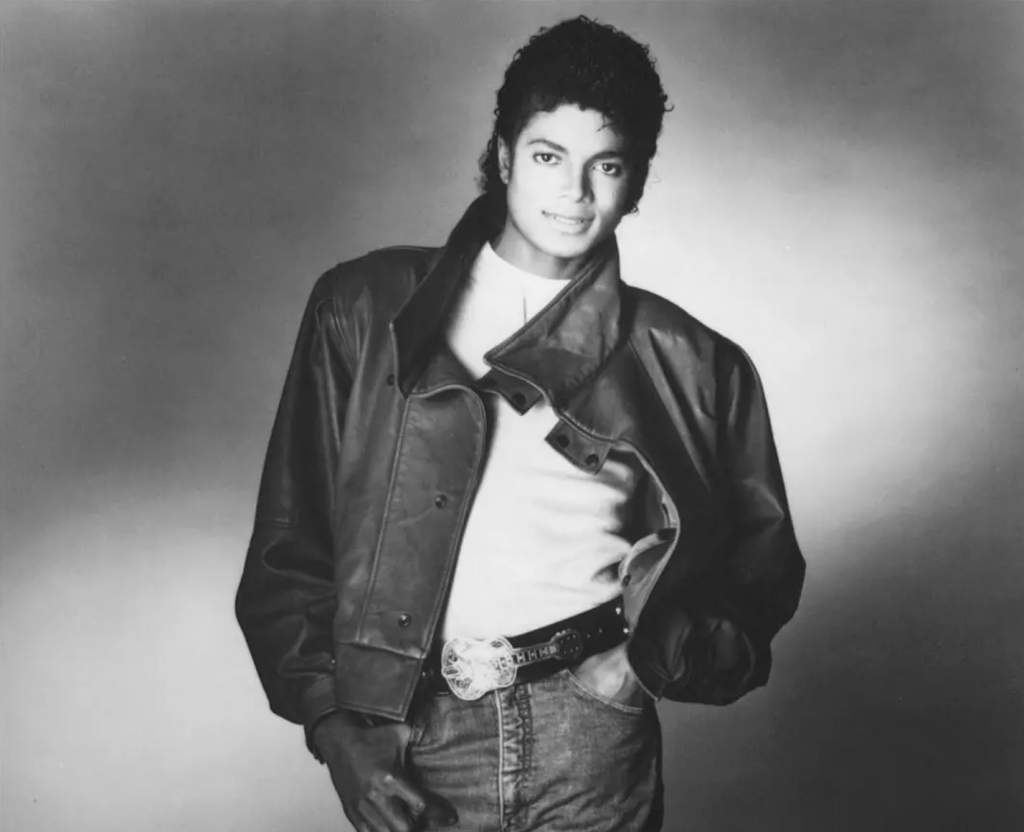

The publishing rights to the Beatles catalog were owned by Michael Jackson. Yes, that Michael Jackson. How Michael came to own the rights is a fascinating story in and of itself (expertly told in a June 2, 2014, article by Forbes staff writer Zach O’Malley Greenburg: Buying The Beatles: Inside Michael Jackson’s Best Business Bet). The TLDR version: Paul McCartney had told Michael Jackson that the real money to be made in the music business was in owning the publishing rights to music catalogs. Jackson was a quick learner and outbid McCartney for the Beatles publishing catalog when Robert Holmes à Court, the Australian tycoon who had previously purchased the catalog, decided to sell it.

During the initial phases of Nike’s attempt to secure the rights for “Revolution,” the publishing catalog was administered by CBS Songs. In the fall of 1986, they had advised W&K that “Revolution” was not available for commercial purposes. The matter would have been put to rest there, but fortunately in November 1986, CBS completed the sale of its music publishing business to SBK Entertainment World Inc. Metaphorically, this gave us another bite of the apple. Those familiar with Nike’s corporate culture know that “Just Do It” and “There Is No Finish Line” are more than ad taglines. They infuse what is expected of employees when presented with an obstacle to overcome—an ethos, if you will. The obstacles here were twofold: CBS’s statement that the song wasn’t available for licensing, and the likelihood that even if we could secure the publishing rights, there was no way Capitol Records would license the song for an ad.

Because this all happened in the late ’80s prior to Google’s existence, finding the right people to talk to would require more sleuthing than it would in today’s world. In an article about how Jackson had acquired the Beatles catalog from Holmes à Court, John Branca was identified as Jackson’s attorney. I contacted one of his partners, Gary Stiffelman, and told him that Nike was interested in securing the rights to “Revolution” for an ad campaign. He directed me to Pat Lucas at SBK. When I initially called Lucas with the request, she told me that she was very familiar with Nike’s advertising and that her 14-year-old son was a huge Michael Jordan fan. This was a good omen.

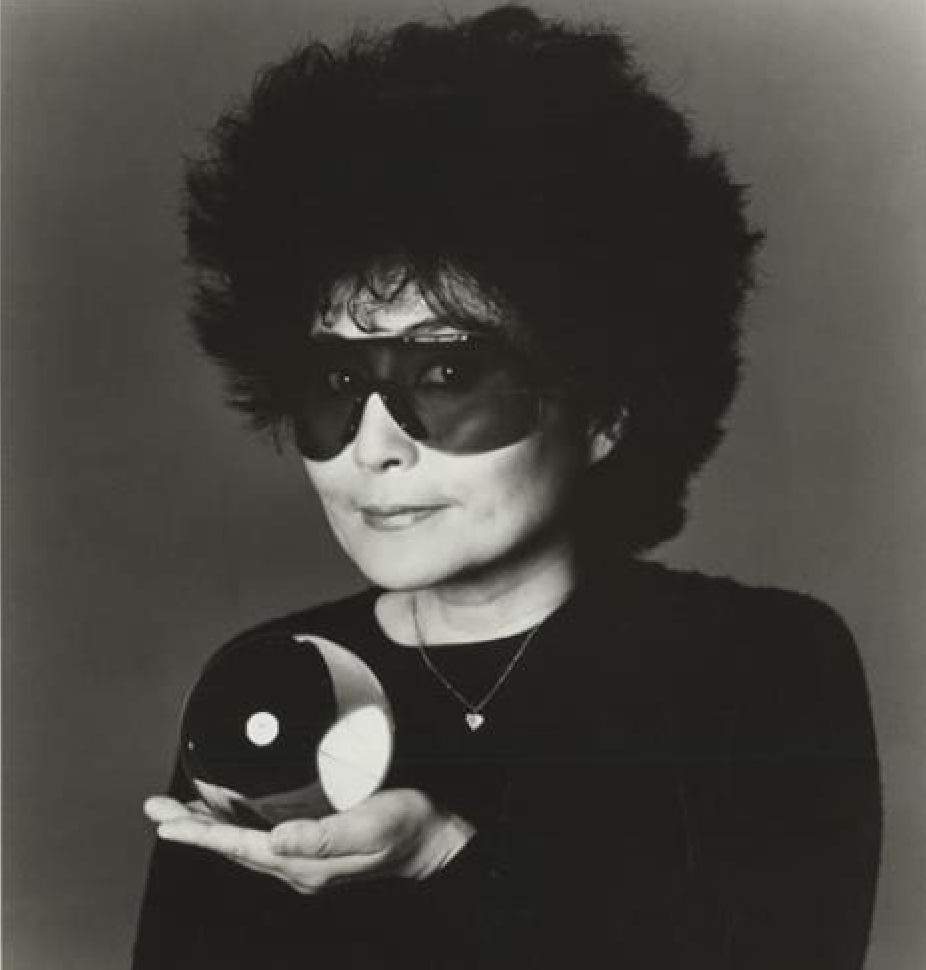

Lucas also told me that although Michael Jackson had the rights to license the music to whomever he wanted to, as a courtesy she would advise Yoko Ono of any potential use of a song that John Lennon had written. I secured an agreement with SBK that they would not license the music to anyone else until March 1, 1987. Lucas then advised me that Ono was in favor of licensing the song for the ad. In addition, Ono suggested that Nike try to secure the rights to the master recording of “Revolution.” That was an interesting twist given our previous inability to secure even a meeting with Capitol Records or its U.K.-based parent company, EMI.

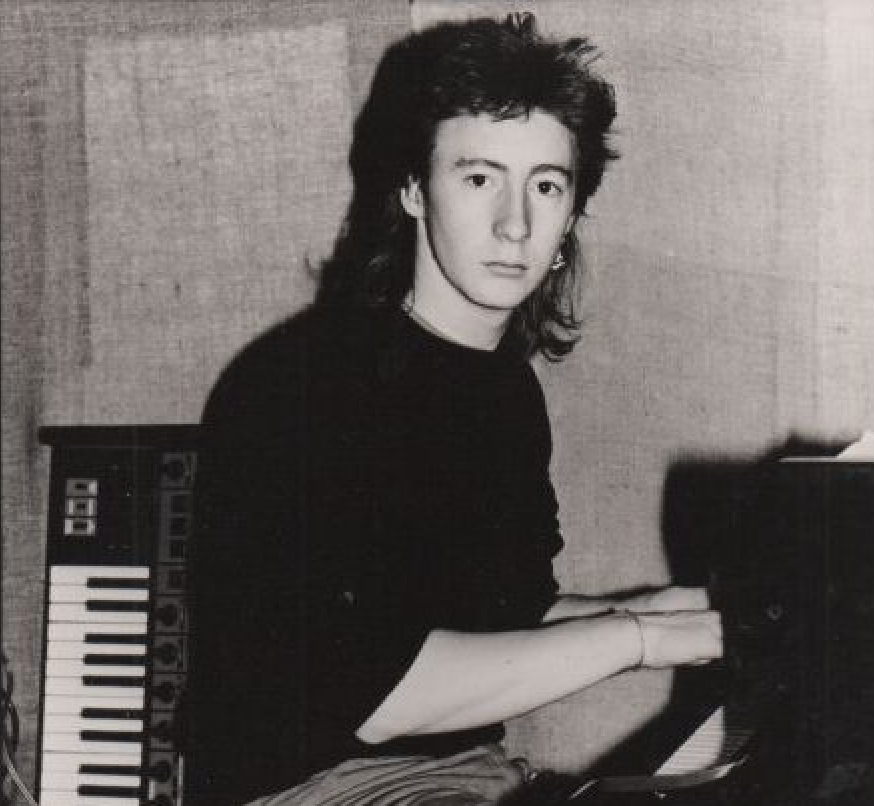

I told Lucas that I had already talked to Capitol and they told me that they were 99.5 percent sure that there would be no way that they would ever license the song. In addition, they were unwilling to even meet with us. I advised Lucas that if we could not license the Beatles’ version of their song, we were considering a number of other artists to re-record it. Among the artists that I mentioned was Julian Lennon, John’s son from his first marriage to Cynthia Lennon. Lucas got back to me a few days later and advised me that Ono’s longtime companion, Sam Havadtoy, would be in California in January and would be willing to set up a meeting with us and representatives from Capitol and EMI about licensing the song. Nearly 30 years would pass before I realized the connection between my suggestion to use Julian Lennon to re-record the song and our eventual success in getting the rights to use the Beatles’ version.

On January 14, Nike ad director Cindy Hale and W&K’s Dan Wieden, Susan Hoffman and Bill Davenport all joined me in Los Angeles for a meeting that Havadtoy had set up with Bob Young (vice president of business affairs for Capitol Records) and Guy Marriott (vice president of business affairs for EMI). Havadtoy opened up the meeting by saying that Ono thought it was a good idea for Capitol to license the master recording to Nike. That 0.5 percent chance that the song would ever be licensed was starting to look considerably improved.

The Capitol/EMI representatives said they had a long-standing policy never to release any of the Beatles’ songs for advertising purposes. The Beatles’ music was the crown jewel of the EMI catalog. I told them that while we would like to use the Beatles version of “Revolution,” it was not crucial for our ad campaign. I had already secured what we needed (i.e., the publishing rights from SBK). I also mentioned that we were considering other artists—including Julian Lennon—for the campaign. Havadtoy then quickly interjected: “Yoko would really like to see this licensing happen.” Although the interested parties (Apple Records, the Beatles and Ono) were in a series of lawsuits with Capitol/EMI, they also had to work together on a number of projects, documentaries, compilation CDs, etc. The tenor of the meeting changed dramatically when Havadtoy expressed Ono’s wish that a deal be done. Without that support, I’m sure there would have been no deal.

The next day, I faxed Havadtoy thanking him for taking the time to meet with us at Capitol. I assured him of our sincere desire to keep intact the integrity of the music and that Nike would in no way imply that the Beatles were endorsing our product. I also pointed out that I sensed my statement that we were in the process trying to get in touch with Julian to see if he wanted to do the song did not sit well with Havadtoy. This being the case, I told Havadtoy that our people in England would cease all efforts to contact Julian.

I told him that if we couldn’t get the Beatles’ version, we’d do a cover with someone else. Someone at W&K thought Richie Havens would be a good choice. I thought so, too. I had seen Havens open at Woodstock in 1969. My buddy and I got tired of the rain and left the next morning. Oops.

The negotiations with Capitol continued, and we were eventually able to strike a deal. In 1987, I gave little or no thought to the impact of my telling Lucas and Havadtoy that we might use Julian to cover the song. Decades later, when I was looking through my old files, I realized how important it was when I found a copy of a 1987 interview Charles Bermant did with George Harrison. The interview covered a wide range of topics. Of particular note:

Bermant: How did it happen that the Beatles song “Revolution” is being used to sell Nike sneakers?

Harrison: From what I understand, Nike was going to use the song and re-record it with Julian Lennon. But Yoko (Ono) got really ticked off at that idea because I don’t think she likes Julian, and she insisted that it be the Beatles version. She has no right to insist that. It’s in the Beatles’ and Apple’s interest not to have our records touted about on TV commercials, otherwise all the songs we made could be advertising everything from hot dogs to ladies’ brassieres.”

It appears that the news that we would not use Julian, which I conveyed to Ono via Havadtoy, didn’t find its way to Harrison. The “strategy” I devised of letting Ono know we might use Julian to cover the song seems to be one of the key factors in Ono’s pushing Capitol to license us the Beatles’ version of the song. To date, 34 years after “Revolution” aired, the Nike ad is still the only ad ever to use the Beatles’ version of one of their songs. We did, however, use John Lennon’s “Instant Karma” in another campaign. More about that later.

-

Julian Lennon -

Michael Jackson -

Yoko Ono

Chapter 3: We Wanted A Revolution And We Got One

Given the proliferation of the use of pop music in advertising over the last three decades, it is hard to imagine or recall the controversy Nike’s use of “Revolution” in an ad caused in 1987.

I was an unabashed Beatles fan. I was 14 years old when the Beatles’ music first made its way to America. I was 15 when they appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show. I knew the history behind Lennon writing “Revolution.” In 1987, music file-sharing did not exist, nor did Spotify or Pandora. There was no iTunes. If you were going to be exposed to the Beatles’ music, it was either because your parents played it around the house or you had a fondness for oldies stations. I thought then, and I believe now, that the use of pop music in advertising can expand the audience for a particular song or artist. I’ve always believed it is one of the particular strengths of W&K that they proposed and asked Nike to go along with doing the unexpected in our ads. When our target audience of 14-to-24-year-olds saw the “Revolution” ad, they were exposed to some music that they might not have otherwise heard. The goal of the ad, of course, wasn’t to expose another generation of consumers to “Revolution.” It was to use the music in a creative way to inspire them to participate in the fitness revolution—and buy Nike products while doing it. Nevertheless, a new generation did become familiar with the song via the ad. And resulting publicity and lawsuit.

Reaction to the television ad was immediate. Hundreds of letters came into Nike. There was no middle ground on the issue. People either loved the ad and the music being used in it or told us they would never buy another pair of Nike shoes. The controversy soon caught the attention of NBC’s Today Show, the leading morning program at that time. Host Jane Pauley expressed a point of view shared by many that the ad’s use of the Beatles’ music had taken away part of her childhood, lamenting that the music was sacred and it shouldn’t have been used in advertising.

Prior to the show, on May 18, 1987, I had told a Today Show representative, “I am glad that The Today Show is trying to understand all sides of the ‘rock music in advertising’ issue. One of the things that the Nike ad was designed to do was to push the concept of fitness.” I may have also mentioned that the surgeon general had recently come out with a study criticizing the health of today’s youth. A lot of things have changed since 1987. The surgeon general concern with the fitness of today’s youth is not one of them.

Nike’s PR department was considerably smaller in 1987. A great number of media calls came in asking about the choice of music or the negotiations that led to securing the rights. Often my exasperated PR colleagues told me, “Thomashow, you got us into this, you can deal with it.”

One of the first issues that came up was why didn’t Nike just use a soundalike instead of the Beatles? In the March 12, 1987, Wall Street Journal, I was quoted as saying, “It detracts from the commercial if viewers sit there thinking, ‘That doesn’t sound quite right,’ and wonder who is singing the song. Nobody ever performed ‘Revolution’ as well as the Beatles did, and it’s Nike’s style to be authentic.”

That was the first and last time I was quoted in The Wall Street Journal. I was, however, quoted in the March 23, 1987, edition of Footwear News. The article was concerned with how we were able to obtain the rights from Capitol to use the Beatles’ master recording of the song. As previously stated, Capitol had nixed the idea of using the Beatles’ master for commercial purposes. Yoko and SBK had managed to set up a meeting between Nike, W&K and Capitol/EMI. We showed them a rough cut of the spot as well as other work W&K had done, including the Honda ad that used Lou Reed singing, “Take a walk on the wild side.” I told Footwear News, “They were visibly impressed with the work. And we convinced them that we had good intentions.” We weren’t looking for an implied endorsement of our shoes, just a good soundtrack for some compelling footage.

My most articulate rationale for why it was an appropriate use of the song was contained in an interview with Kathy Haight in the entertainment and travel section of the June 21, 1987, Charlotte Observer. I said, “Any music has a historical context in which it first came out. Brahms or Beethoven’s first audiences might’ve been a king and queen and 25 members of the court. Should their work stay in that historical context or should it have wider applications? Can music or any piece of art have different meanings or different applications at different historical times? I think it can without undercutting the value it originally held for people when they first heard it.”

Haight wrote, “OK. No one’s going to argue that staying in shape isn’t a worthy goal. But as Thomashow says, the ‘Revolution’ commercial is selling shoes and it’s also selling a concept. There is a fitness revolution and a revolution in (athletic footwear) technology which Nike is at the forefront of.”

I went on to say, “A writer from the LA Reader said when he first heard ‘Revolution’ he was being tear-gassed at an antiwar demonstration at the University of Wisconsin. Do I feel, 20 years later, that using that song takes away from the political convictions people had or makes their experience less meaningful? No, I don’t think so.”

References to the use of the music in the ad turned up everywhere. The popular Bloom County comic strip depicted one of the characters telling his dad that, “They’re selling shoes on TV with John Lennon’s song ‘Revolution.’” He goes on to say, “Can’t you just guess what other song someone would pick to sell the NRA?” His dad, who is lying in bed, trying to end the conversation, pipes up, “‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’?” I’m pleased to see that the NRA has never been able to successfully license this or any other Beatles music for their campaigns.

I contacted Bloom County’s creator, Berke Breathed, and asked if we could have a signed copy of the strip. He was unable to do this but did send me a nice letter: “Congratulations on your coup with the Nike revolution! Definitely an inspiration to those of us who like to nestle our toes in elegant comfort. Obviously the residents of Bloom County await the next advertising extravaganza with bated breath. Give Yoko a squeeze for me.”

There were headlines like the May 18, 1987, Time article by Jay Cocks: “Wanna Buy A Revolution?: The Beatles Shill For Sneaks As Mad. Ave Rocks Out.” The Globe And Mail contributed “Turning Pop Classics Into Ads Has Rock Fans Singing The Blues.” One of the most vocal critics of the use of the song in the ad was John Wiener, a professor in the history department at the University of California, Irvine.

Wiener appeared on the previously mentioned Today Show. He also wrote an interesting article in the May 11, 1987, issue of The New Republic. The article is titled “Beatles Buy-out,” and in it, he gave an extensive history of the song and what Lennon was influenced by when he wrote it. He also stated that “Beatles fans are outraged” by its use in the ad. To be fair, he also pointed out that “Neither Ono or McCartney objected to Jackson’s licensing of ‘Revolution’ for the Nike ad.” He then went on to quote Ono as saying, “John’s song should not be part of a cult of glorified martyrdom. They should be enjoyed by kids today. This ad is a way to communicate John’s song to them, to make it part of their lives instead of a relic of the distant past.” Ono went on to say that, “Sports shoes are part of a fitness consciousness that is actually better for your body than some of the things we were doing in the ‘60s.” Wiener pondered what would come next after Nike using ‘Revolution’ in an ad. He wondered whether it would it be “‘Give Peace A Chance’ selling Star Wars?” (Presumably, he meant Ronald Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, not the George Lucas movie franchise.) Or, perhaps, “‘Happiness Is A Warm Gun’ licensed to the National Rifle Association?”

I wrote a letter to Wiener asking for the empirical data for his statement that Beatles fans were outraged. I pointed out that the feedback we were getting at Nike was clearly that most people enjoyed the ad and understood its message of pushing people to adopt a fitness lifestyle. I did acknowledge that there were some folks (a minority) who expressed the view that their adolescence was somehow devalued or that the Beatles’ music was ripped off. I pointed out that from my discussions with Michael Jackson’s representatives, I suspected it would be a while before we see Beatles songs, even as covered by other artists, used to promote Star Wars, the NRA, the Contras, underarm deodorant, pantyhose or other products. I think given that no Beatles masters have been used since the 1987 Nike ad shows that those who felt the catalog would be abused were mistaken. Jackson’s representatives have been very judicious in the use of what Beatles songs could be made available for advertising. Capitol and EMI have never chosen to allow the Beatles’ version of any of their songs to be used in an ad.

Another vocal critic of the use of the music in advertising was Chris Morris, the LA Reader’s rock critic. I saw him quoted in Wiener’s New Republic article. I also saw him on CBS Evening News, where he made the statement that Chairman Mao never wore sneakers. I sent off a letter to him on May 14, 1987, in which I said, “While I had no way to verify the fact that Mao didn’t wear sneakers, I suspect that if he didn’t, the reason was because Nike did not begin producing sneakers in China until the 1980s. If we had, he likely would have worn them and the Long March wouldn’t have seemed quite so long.” I also went on to point out that although Mao never had the opportunity wear our sneakers, his disciples had. I sent him a copy of a photo from Time magazine of Premier Zhao and pointed out he was easy to spot as he was the one wearing Nike sneakers in the middle of the picture. I closed my letter, “It is our position at Nike that reasonable well-intentioned people can differ as to ‘appropriate uses of music.’ Please take this letter in the spirit for which it is intended.”

Strangely enough, I never heard back from him.

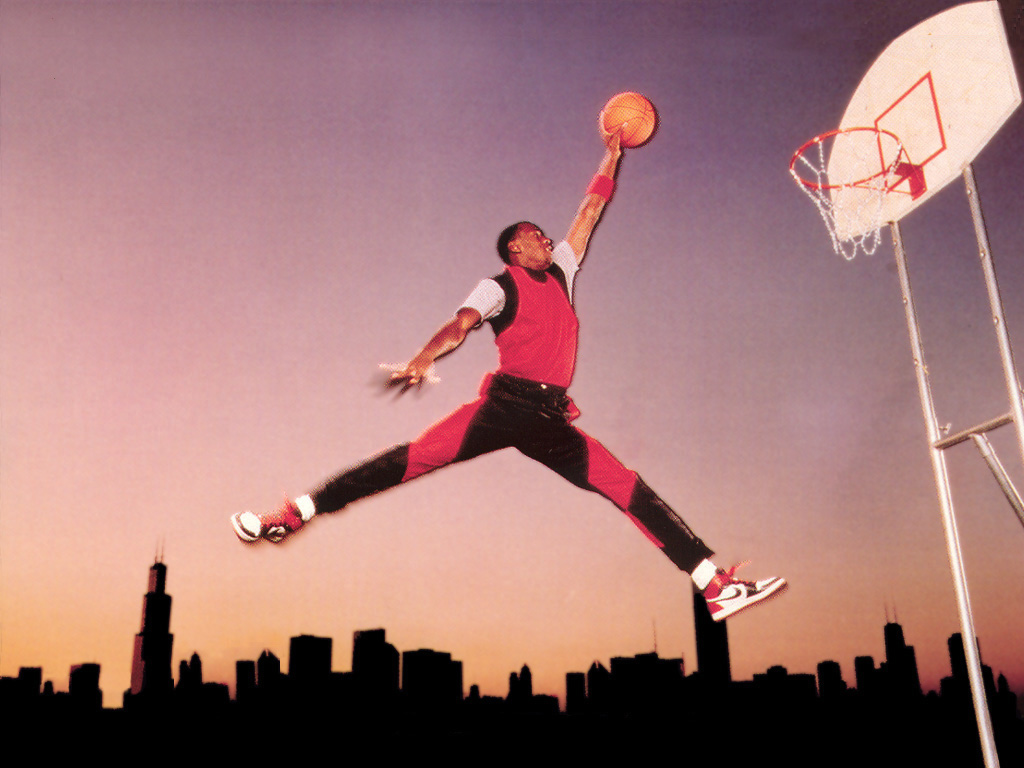

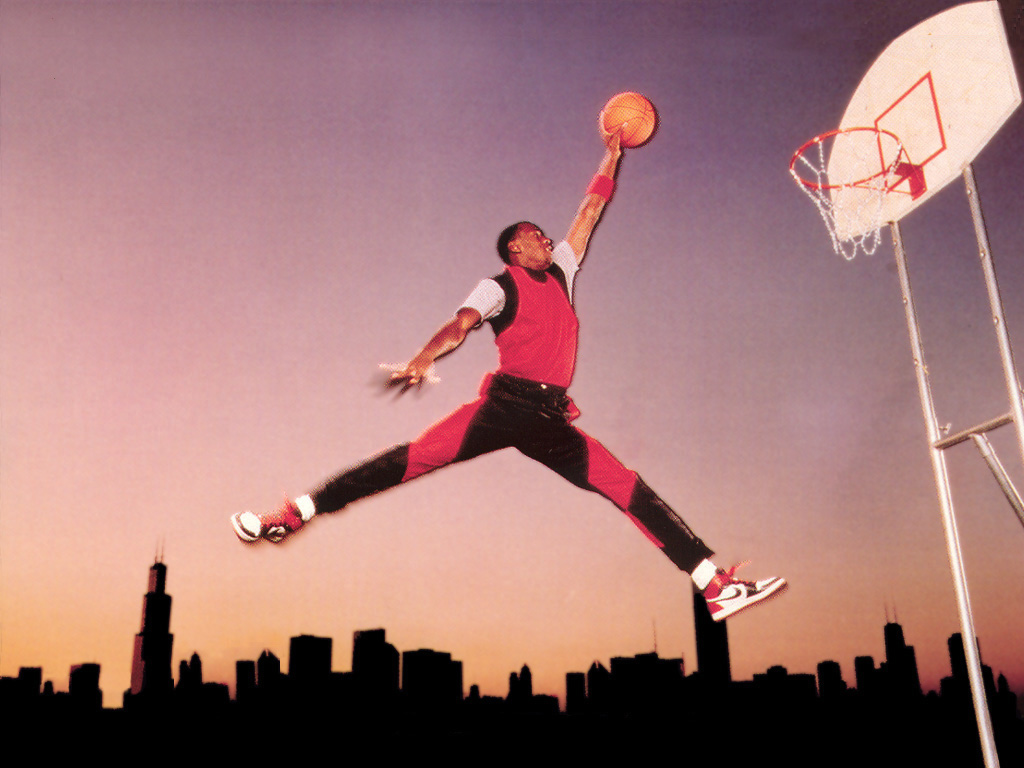

Here’s another little footnote to the “Revolution” story. Nike had a mini poster with the famous image of Michael Jordan jumping over the Chicago skyline and dunking on an outdoor court. The image became the Jumpman logo for Air Jordan. It is the second most impactful silhouette of a basketball player, surpassed only by the image of Jerry West as the NBA logo. We asked Jordan if he wouldn’t mind doing something nice for the folks who helped us get the music. He signed one of the mini posters for Yoko, Havadtoy and Sean Ono Lennon, “Thanks for helping my friends at Nike with ‘Revolution,’ Michael Jordan.” He also signed one for Michael Jackson.

Of all the letters we received during the “Revolution” campaign, two of my favorites stand out. The first was from a Mary Matheson of Minneapolis, dated April 27, 1987: “Dear people: I feel I’ve seen the best commercial of the 1980s. I’m talking about your 30 and 60 version of your Nike Air 10 tennis shoe with the Beatles ‘Revolution’ soundtrack. It can’t get any better than that. Congratulations!”

My absolute favorite came from Sarah Henn, a seventh-grade student at St. Thomas Aquinas School in Indianapolis: “My class has recently been studying advertising techniques. Your commercial for Nike shoes is great! Putting the song ‘Revolution’ in your commercial brings back memories for my parents. I really enjoy your commercial. Please continue advertising your product like you do now.”

Despite all the controversy, or perhaps because of it, the “Revolution” ad campaign was a seminal event in Nike’s advertising history. The shoe featured in the ad and launched by the campaign, the Air Max, had a phenomenally successful introduction. Nike’s commitment to promoting fitness was evident in the campaign and has continued as a hallmark of Nike ever since. The ad showed the power of a well-crafted message. It also showed what could happen when Nike’s premier athletes were matched up with elements of pop culture in an unexpected fashion.

And it taught Nike a valuable lesson: Even when you are sure you’ve covered all your legal bases, you can still be sued.

Chapter 4: We Got Our Revolution And A Lawsuit, To Boot

By most measures, the ad campaign had been a home run. The introduction of the Air Max was all that could’ve been hoped for. The ad generated a tremendous amount of commentary. Most of the direct feedback we were getting from consumers was that they harbored no ill will toward Nike for using a Beatles song in our ad campaign. The truth of this was probably reflected in the fact that customers were voting with their discretionary dollars. And vote they did—it was one of the most successful product launches in Nike’s history.

The yin of the ad campaign started in March when we first began to run the ad, which continued airing into July. The yang arrived abruptly in July, in the form of a lawsuit filed by Apple Records against Nike, Capitol, EMI and W&K. At the time, it seemed like an honor for Nike to be the first party named in the Apple suit. Turns out there was a reason for listing us first. More on that later.

I probably wasn’t as concerned about the lawsuit as I should have been, and it soon became apparent that there had been one major miscalculation. It had nothing to do with whether I had done anything wrong in licensing the music from Michael Jackson and Capitol/EMI. I’d negotiated with the appropriate rights holders. My mistake was in not knowing the contentious relationship that Apple had had with Capitol and EMI over the years. It is a fascinating history.

The most interesting explanation of the relationships can be found in an Aug. 9, 1987, Washington Post article by Mark Potts titled “It’s A Long And Winding Lawsuit,” excerpted below:

“But 25 years after the Beatles signed their first record contract, a bitter, long-running legal dispute is under way between lawyers for the group and EMI-Capitol. The charge: The record company has systematically shortchanged the group on record royalties for years …

“‘The Beatles do not enjoy litigation, and would much prefer to avoid it, but there are some situations where it really is the only thing to do,’ said Leonard Marks, the attorney for Apple Records Inc., the company set up by the Beatles in 1968 to handle their affairs and that now is pressing the case against the record company. ‘The Apple companies and the Beatles had been cheated.’

“But officials of Capitol and EMI adamantly deny the charges. And in an industry that is traditionally tight-lipped about contract disputes, they have been unusually outspoken about the case. Executives of EMI-Capitol portray the dispute as a simple contract-interpretation problem that is being overzealously pursued by Marks.

“’The original lawsuit really represents different interpretations of contractual situations between EMI Records and Capitol in their many agreements in the past with Apple,’ Bhaskar Menon, Capitol’s chairman, said in an interview last week. ‘We see not the slightest value or benefit of pursuing this long, drawn-out, dust-laden series of litigations … In some quarters, there is somebody who is benefiting from this. I can certainly say we aren’t, and I can’t imagine the Beatles themselves are’ …

“The case has been highlighted by some remarkable allegations, including those surrounding the disappearance or destruction of 19 million Beatle records, charges that some of these were sold ‘out the back door’ of Capitol factories to avoid royalty payments, and hints of organized crime involvement in the record industry.”

Cynics might suggest it was the attorneys benefitting from the litigation. I sat with our attorneys in Leonard Marks’ office. He told me that “this lawsuit will put my kids through college.” I’m not altogether sure whether it did, but I know the lawsuit was a key event in Nike’s marketing history. Perhaps it really was a “win-win.”

The Washington Post article went on to point out that “the 1979 case has spawned two related, newer suits, filed [in July 1987] … Apple alleges that Capitol wrongfully licensed the recording of the Beatles song ‘Revolution’ to Nike, Inc. for use in a shoe commercial.’ Capitol has adamantly denied those charges as well, calling them ‘frivolous’ attempts by Marks to call attention to the broader case.”

A peculiar twist in the unfolding lawsuit drama was, The Post pointed out, that “Yoko Ono is participating in the suit against Capitol and Nike over the ‘Revolution’ commercial even though she was quoted in news stories earlier this year as approving of the song’s use by Nike. Marks said Ono’s interest in the publishing rights to the song divides her loyalties on the Nike case.”

The article goes on say that Nike viewed it as being caught in the middle of the long-standing legal battles between Capitol and Apple. Aside from securing the rights to the music initially, my biggest contribution to this great tale is I suggested the following line to be delivered by Phil Knight at his press conference in New York, where he invited the surviving Beatles as well as Ono to a one-on-one meeting to discuss Nike’s use of the ad. My line was: “We believe Nike is a party to the suit solely because ‘Beatles Sue Nike’ makes much better headlines than ‘Apple Sues EMI Capitol For The Third Time.’”

My mistake in the whole affair was, despite being an avid Beatles fan my whole life, I was, during my second year at law school, more intent on plowing through my course load than in researching and reading about a 1979 lawsuit filed by Apple against Capitol EMI that would play a significant factor in my Nike career, eight years later.

But back to the suit. I wasn’t too concerned about it. We had done nothing wrong from a legal perspective. In addition, I had to feel great about our prospects for winning, when we were represented by accomplished NYC intellectual-property lawyers, including Gerald Sobel and his colleague Tom Smart. It did not take long for the media to rush to cover this epic battle between the world’s greatest rock band and the most exciting and successful athletic footwear and apparel company in the world. The Aug. 5, 1987, USA Today contained a headline in its business section stating “Beatles Battle, Part Two,” with a nice picture of Phil Knight and the caption, “Says Nike got permission to use song.” Another part of the same paper paid homage to Nike’s running heritage and one of the Beatles’ classics by saying, “Beatles Vs. Nike Runs A Long And Winding Road.” A New York Times article on Aug. 5, 1987, from the living section noted that “Nike Calls Beatles Suit Groundless.” On Aug. 5, 1987, the New York Post headline was “Nike Boss Wants Fab Four” with a picture of the Beatles.

An Aug. 5, 1987, Daily News article in the business section was headlined “Nike Rebels Against Revolution Charges.” Another Daily News headline was “What A Revolting Predicament,” which featured a cartoon image of the Air Max stomping down on the heads of upwardly looking members of the Fab Four.

The broadcast media provided an interesting case study. Often, you would see a news anchor with a background screen split diagonally. On the top part was an image of the Beatles; on the bottom part was either the name Nike or the swoosh logo. I’ve often thought that people are more visual than auditory. Viewers heard the news anchor talking, often accompanied by a playing of the ad. What I think registered was that somehow Nike and the Beatles were connected or partnered. This was reinforced by the visual. The fact that the connection was that the Beatles had sued Nike likely was undercut by the visual imagery.

Just a theory. However, it isn’t a theory that “Beatles Sue Nike” was a great headline. Much better than “Apple Sues EMI Capitol For The Third Time.” It explains why Nike was the first party named in the lawsuit.

Nike’s press release about the lawsuit was a classic. It appeared in USA Today. Under the “CAN WE TALK” banner, it stated:

“You may have heard reports that Nike is being sued by the Beatles.

That’s not exactly true.

Nike, along with our ad agency and EMI Capitol Records, is being sued by Apple Records. Apple says we used the Beatles recording of ‘Revolution’ without permission.

The fact is we negotiated and paid for all the legal rights to use ‘Revolution’ in our ads. And we did so with the active support and encouragement of Yoko Ono Lennon. We also believe we showed a good deal of sensitivity and respect in our use of ‘Revolution’ and how we’ve conducted the entire campaign.

So why are we being sued? We believe it’s because we make good press. ‘Beatles sue Nike’ is a much stronger headline than ‘Apple sues EMI Capitol for the third time.’ Frankly, we feel we’re a publicity pawn in a long-standing legal battle between two record companies.

But the last thing we want to do is upset the Beatles over the use of their music. That’s why we’ve asked them to discuss the issue with us face-to-face. No lawyers, critics or self-appointed spokespersons.

Because the issue goes beyond legalisms. This ad campaign is about the fitness revolution in America, and the move toward a healthier way of life.

We think that’s a message to be proud of.”

When the lawsuit was filed, with an ask for $15 million in damages, Dan Wieden, the co-founding partner of W&K, asked Phil Knight whether Nike would indemnify W&K in the event the lawsuit was lost. A big judgment would be a crippling outcome for the agency. Phil told Dan that W&K was playing in the big leagues now and there would be no indemnification forthcoming. What you have to love about the W&K folks is their ability to keep their sense of humor in the face of potential financial or other adversity. The invitation to their annual Thanksgiving party was a classic.

The front was all in bold caps on a black background. It said:

“In 1987 Wieden Kennedy lost a $12 million national account and was sued by the most popular rock ‘n’ roll group in history.”

The backside of the invitation showed a shot glass partially filled and had the closing line all in caps quote:

“We don’t know about you, but we could use a drink.”

No discussion of the “Revolution” ad campaign and the following lawsuit would be complete without referencing a 1987 article in The National Enquirer. It had the headline “Michael Jackson And Ringo Starr Both Claim They’ve Seen John Lennon’s Ghost!” The article stated: “Jackson told a close friend: ‘I looked up and suddenly saw the image of Lennon in my room. I couldn’t believe my eyes! I could see right through him, but he still looked so real! The only thing different was he wasn’t wearing his glasses. John looked very peaceful and happy. He wore a plain shirt, jeans with patches and no shoes. At first, I couldn’t say anything. I just stared. But then he spoke, saying: ‘Let my music live.’ I’d been thinking about the Nike ad all day. I immediately understood what he was telling me.’

“Michael felt Lennon was advising him to go ahead with the Nike deal, and that’s exactly what he did. Said the source close to Jackson, ‘Michael has been sharply criticized for that decision. Even Paul McCartney expressed his immense displeasure, and Beatles fans were outraged. But Michael feels Lennon was backing him in this controversial decision. He said, “I know a lot of people are angry, but I wish they could understand that this is what John wants. John’s spirit lives in the songs. By doing new things with the songs it’s like allowing John to keep living.”’

EMI/Capitol eventually settled their lawsuit. I don’t know what they paid to do so, and I don’t really care. Nike and W&K paid nothing, except our own attorney fees. This was as it should be. We had done nothing wrong. We were basically a pawn in a lawsuit between two record companies.

An interesting point needs to be made here. We had made clear to Ono’s attorney that if the lawsuit continued, we’d be suing Yoko for fraud in the inducement, because but for her active involvement in helping us secure the license, no license would have been secured. We’d have moved on to another artist. We were not privy to the eventual settlement discussions between Capitol, EMI and Apple. It is safe to assume that the threat of Nike suing Ono likely factored into the discussions.

I’ll let Ono have the last word regarding Nike’s “Revolution” campaign, from an interview she gave to Ben Fong-Torres of the San Francisco Chronicle, on Sept. 18, 1987. “First, [McCartney] and I didn’t have a right to say yay or nay. Michael Jackson was very considerate. He said no to 50 offers until this one, which seemed tasteful enough. If I thought it was really detrimental to the music, I would’ve fought vigorously. But the fact that the song is going out to the world is great. Besides, it’s a ‘revolution’ to wear sneakers rather than high-heeled shoes.”

Postscripts

Getting sued by Apple—which had George, Paul, Ringo, Yoko and Neil Aspinall as its board members at the time—was not the last time we had the opportunity to deal with Yoko. In a May 25, 1988, USA Today article under the headline “Imagine: Yoko Ono And TV ad,” Stuart Elliott wrote, “Yoko Ono is singing a different tune when it comes to using John Lennon’s music in commercials. Ono, Lennon’s widow, joined the other Beatles last year in a lawsuit against Nike Inc. for using the song ‘Revolution’ in commercials for its running shoes. But now she and her son by Lennon, Sean, are appearing in the Japanese commercial set to Lennon’s trademark ‘Imagine.’

“Ono and Sean play catch in a New York park in the ad for Kokusai Denshin Denwa, Japan’s long distance telephone company. Ono never mentions the company in the ad. Shukan Shincho, a weekly Japanese magazine, says Ono, 55, was paid $320,000-$400,000. A spokesman for the phone company says he didn’t know about the Nike suit. He reports no complaints from Lennon fans about using ‘Imagine.’

“Ono and ex-Beatles George Harrison, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr are pressing a $15 million suit against Nike on the grounds that the company used their ‘persona and goodwill’ without permission. Nike paid $250,000 to Michael Jackson, who owns rights to much of the Beatles music, and $250,000 to EMI Capitol Records to use master recordings of ‘Revolution.’ Nike has decided not to use ‘Revolution’ anymore.”

Actually, the decision to stop running the ad had nothing to do with the lawsuit. The ad had simply run its course.

Before moving on, I need to add the following. I was doing something in the kitchen while on the television, CNN had a 2016 New Hampshire primary-night report. I wasn’t paying attention, but I’m pretty sure that when Donald Trump walked out to address his followers, the music accompanying him was the Beatles’ “Revolution.” I suspect Trump was trying to appeal to baby boomers using that music to position himself as the harbinger of a new revolution in American politics. I don’t know whether anyone representing the Beatles’ interests sent Mr. Trump a cease-and-desist letter, but one can guess.

In another interesting development, Paul McCartney sued Sony Music in early 2017 to get the publishing rights back from all the songs he wrote. According to the BBC, “McCartney has been trying to get the songs back since he was outbid for them by Michael Jackson in 1984/85. Jackson’s estate sold its interest to the publishing rights to Sony in 2016. Yoko had previously sold Lennon’s estate’s interest to Sony. Sir Paul’s suit hinges on U.S. copyright law, but there is an open question whether U.S. or U.K. law will control the issue.”

Five years after “Revolution,” it was Nike’s turn to use a John Lennon song in an ad campaign. There were no hard feelings on Yoko or Nike’s part about the “Revolution” lawsuit. In fact, the negotiations for the use of “Instant Karma” could not have been better. But I’ll save that story for some other time.

—as told to Corey duBrowa